Threat intel isn’t only enrichments; it’s detections too.

Many of you will be familiar with detection languages in SIEMs to search for malicious events. Detection rules can be as simple as searching for an IP address. Or be more complex, looking for behaviours and patterns alongside observable like IP addresses.

In STIX 2.1, an Indicator must include a pattern (and pattern_type). That pattern can be a STIX expression or another detection language.

This guide covers:

- Supported pattern types in Indicators

- STIX pattern syntax (expressions, operators, qualifiers)

- Validation & testing (pattern validator + matcher)

- Representing matches with Sighting + Observed Data

Pattern types (aka detection languages) you can embed

The Indicator’s pattern_type can be any from the STIX vocabulary, e.g.:

stix— the STIX pattern language (what we’ll focus on)sigma,snort,suricata,yara,pcre

For example, to put a Sigma rule inside an Indicator: set pattern_type="sigma" and put the rule YAML in pattern (JSON encoded).

STIX Pattern Types

The stix pattern_type is a detection pattern language defined in the STIX specification.

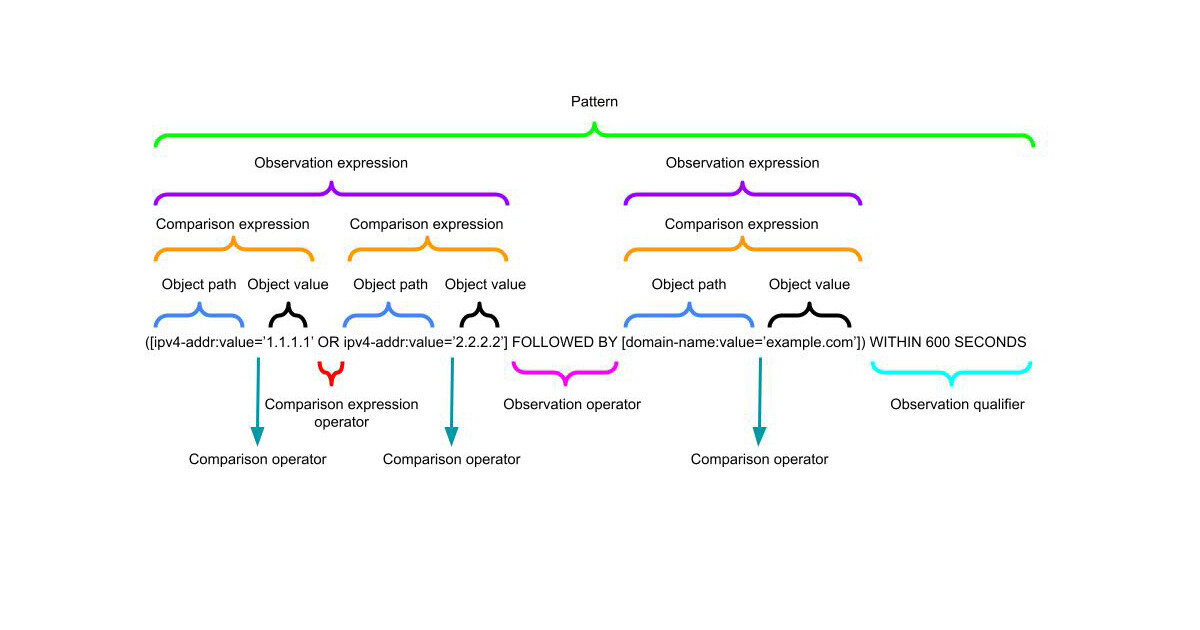

Here is the general structure of a STIX Pattern;

A STIX pattern is built from:

- Comparison Expressions — e.g.

[ipv4-addr:value = '198.51.100.1'] - Comparison Operators —

=,!=,>,>=,LIKE,IN, etc. - Observation Operators — AND, OR, FOLLOWEDBY

- Qualifiers —

WITHIN,START,STOP,REPEATS

Think in layers:

[ comparison ] (AND/OR) [ comparison ] FOLLOWEDBY [ comparison ] QUALIFIER

Comparison Expressions and Operators

Comparison Expressions are the fundamental building blocks of STIX patterns.

They take an Object Path and Object Value (using SCOs).

The simplest detection using STIX Patterns would be to detect an observable, e.g.

[ipv4-addr:value='198.51.100.1']

This uses the ipv4-addr object types value attribute equal to 198.51.100.1.

The ipv4-addr SCO in question would look like;

{

"id": "ipv4-addr--2b3e2c17-3144-5591-9c88-a605220f8c0c",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"type": "ipv4-addr",

"value": "198.51.100.1"

}

You can use a range Comparison Operators in addition to equals (=). Does not equal (!=), is greater than (>), is less than or equal to (>=), etc.

[directory:path LIKE 'C:\\Windows\\%\\foo']

In the above example I am using the LIKE Comparison Operator. You will notice it is possible to pass capture groups. In the example above % catches 0 or more characters.

As such a pattern would match (be true) if directory:path C:\Windows\DAVID\foo OR C:\Windows\JAMES\foo, etc. was observed.

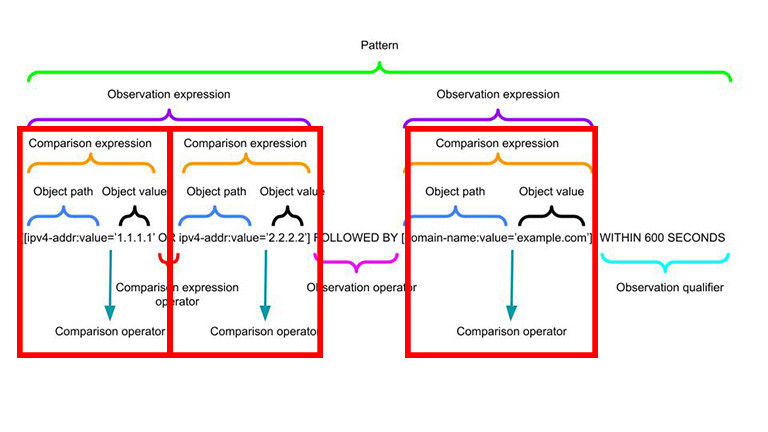

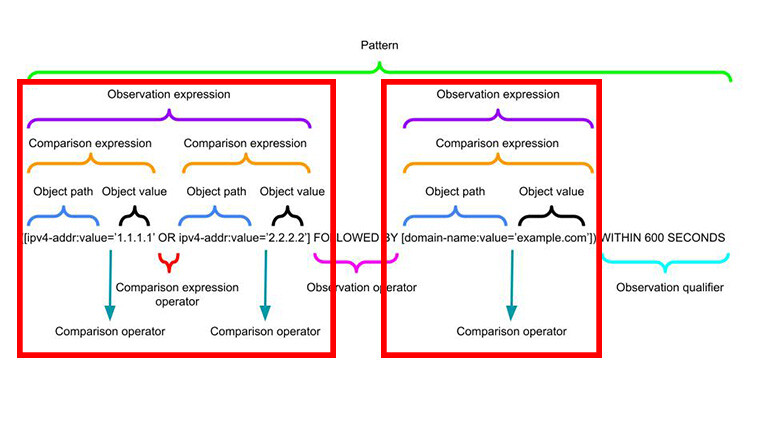

Observation Expressions, Operators and Qualifiers

Multiple Comparison Expressions can joined by Comparison Expression Operators to create an Observation Expression.

The entire Observation Expression is captured in square brackets [].

For example, a pattern to match match on either 198.51.100.1/32 or 203.0.113.33/32 could be expressed with the OR Comparison Expression Operator:

[ipv4-addr:value='198.51.100.1/32' OR ipv4-addr:value='203.0.113.33/32']

Changing the Comparison Expression Operator to an AND makes the pattern match on both 198.51.100.1/32 and 203.0.113.33/32:

[ipv4-addr:value='198.51.100.1/32' AND ipv4-addr:value='203.0.113.33/32']

Observation Expressions can also be joined using Observation Operators.

In the following example there are two Observation Expressions joined by the Observation Operator FOLLOWEDBY;

[ipv4-addr:value='198.51.100.1/32'] FOLLOWEDBY [ipv4-addr:value='203.0.113.33/32']

The FOLLOWEDBY Observation Operator defines the order in which Comparison Expressions must match. In this case 198.51.100.1/32 must be followed by 203.0.113.33/32. Put another way, 198.51.100.1/32 must be detected before 203.0.113.33/32.

Observation Expression Qualifiers allow for even more definition at the end of a pattern.

You can define WITHIN, START, STOP, and REPEATS Observation Expression Qualifiers.

The following example requires the two Observation Expressions to repeat 5 times in order for a match;

([ipv4-addr:value='198.51.100.1/32'] FOLLOWEDBY [ipv4-addr:value='203.0.113.33/32']) REPEATS 5 TIMES

Here is another example that is very similar to a pattern used for malware detection;

([file:hashes.'SHA-256'='ca978112ca1bbdcafac231b39a23dc4da786eff8147c4e72b9807785afee48bb'] AND [win-registry-key:key='hkey']) WITHIN 120 SECONDS

Here if the file hash Observation Expression and a Windows Registry Observation Expression are true within 120 seconds of each other then the pattern matches.

Precedence and Parenthesis

Operator Precedence is an important consideration to keep in mind when writing Patterns.

Consider the following Pattern:

[ipv4-addr:value='198.51.100.1/32'] FOLLOWEDBY ([ipv4-addr:value='203.0.113.33/32'] REPEATS 5 TIMES)

Here, the first Observation Expression requires a match on an ipv4-addr:value equal to 198.51.100.1/32 that precedes 5 occurrences of the Observation Expression where ipv4-addr:value equal to 203.0.113.33/32.

Now consider the following Pattern (almost identical to before, but notice the parentheses):

([ipv4-addr:value='198.51.100.1/32'] FOLLOWEDBY [ipv4-addr:value='203.0.113.33/32']) REPEATS 5 TIMES

The first Observation Expression requires a match on an ipv4-addr:value equal to 198.51.100.1/32 followed by a match on the second Observation Expression for an ipv4-addr:value equal to 203.0.113.33/32, this pattern must be seen 5 times for a match.

Helpful tools to create and validate STIX Patterns

STIX Pattern Validator

The STIX 2 Pattern Validator from OASIS is a great tool in checking your patterns are written correctly.

Simply run the STIX 2 Pattern Validator script by declaring your Pattern…

mkdir stix2-patterns

python3 -m venv stix2-patterns

source stix2-patterns/bin/activate

pip3 install stix2-patterns

validate-patterns

Enter a pattern to validate: [file:hashes.md5 = '79054025255fb1a26e4bc422aef54eb4']

PASS: [file:hashes.md5 = '79054025255fb1a26e4bc422aef54eb4']

Enter a pattern to validate: [bad pattern]

FAIL: Error found at line 1:5. no viable alternative at input 'badpattern'

CTI Pattern Matcher

If you are trying to see if content in an Observed Data SDO matches an existing STIX Pattern (i.e. you have detection coverage for it) you can use the CTI Pattern Matcher.

Lets start by creating an Observed Data SDO, and two related SCOs;

{

"type": "observed-data",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "observed-data--699546f4-6d73-4a35-a961-181a34fa3b14",

"created": "2016-04-06T19:58:16.000Z",

"modified": "2016-04-06T19:58:16.000Z",

"first_observed": "2015-12-21T19:00:00Z",

"last_observed": "2015-12-21T19:00:00Z",

"number_observed": 2,

"object_refs": [

"ipv4-addr--dc63603e-e634-5357-b239-d4b562bc5445",

"domain-name--dd686e37-6889-53bd-8ae1-b1a503452613"

]

}

{

"type": "ipv4-addr",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "ipv4-addr--dc63603e-e634-5357-b239-d4b562bc5445",

"value": "177.60.40.7"

}

{

"type": "domain-name",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "domain-name--dd686e37-6889-53bd-8ae1-b1a503452613",

"value": "google.com"

}

The CTI Pattern Matcher accepts “A file containing JSON list of STIX observed-data SDOs” (in a STIX bundle). Lets create that objects-bundle.json;

{

"type": "bundle",

"id": "bundle--cb06ef7f-acb8-46b6-98e1-27c6fe8d23c2",

"objects": [

{

"type": "observed-data",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "observed-data--699546f4-6d73-4a35-a961-181a34fa3b14",

"created": "2020-01-01T00:00:00.000Z",

"modified": "2020-01-01T00:00:00.000Z",

"first_observed": "2020-01-01T00:00:00.000Z",

"last_observed": "2020-01-01T00:00:00.000Z",

"number_observed": 2,

"object_refs": [

"ipv4-addr--dc63603e-e634-5357-b239-d4b562bc5445",

"domain-name--dd686e37-6889-53bd-8ae1-b1a503452613"

]

},

{

"type": "ipv4-addr",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "ipv4-addr--dc63603e-e634-5357-b239-d4b562bc5445",

"value": "177.60.40.7"

},

{

"type": "domain-name",

"spec_version": "2.1",

"id": "domain-name--dd686e37-6889-53bd-8ae1-b1a503452613",

"value": "google.com"

}

]

}

And lets write a pattern I know matches, and does not match, and store it to patterns.txt

[ipv4-addr:value='177.60.40.7']

[domain:value='microsoft.com']

So if I pass both of these to stix2-matcher;

mkdir stix2-matcher

python3 -m venv stix2-matcher

source stix2-matcher/bin/activate

pip3 install stix2-matcher

stix2-matcher --patterns patterns.txt --file objects-bundle.json --stix_version 2.1

MATCH: [ipv4-addr:value='177.60.40.7']

NO MATCH: [domain:value='microsoft.com']

Which brings us to a slight tangent; how to use Observed Data SDOs.

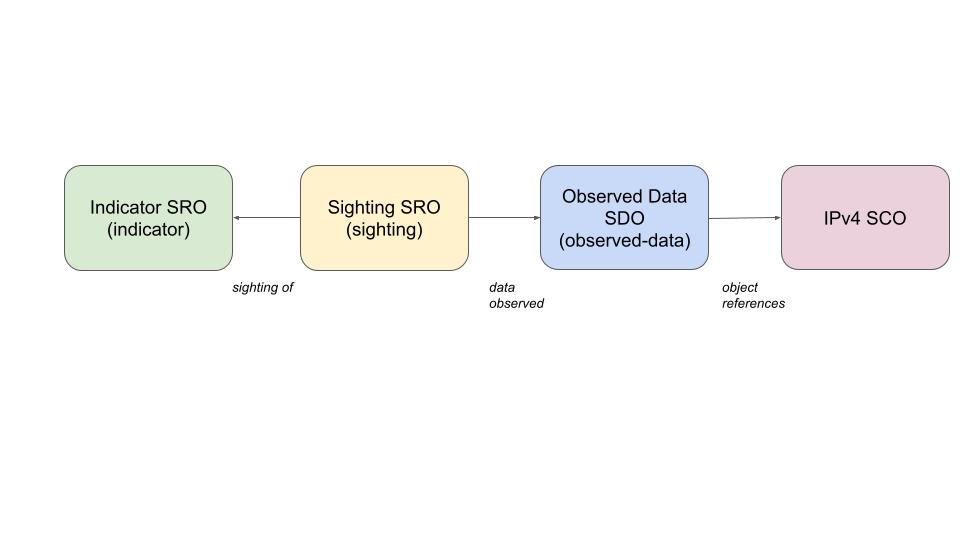

Representing Pattern Matches as Sighting SROs

Now you have seen how Patterns can be used, detections (aka sightings) of these patterns need to modelled.

If you start to use STIX Patterns for threat detection, you will probably want to represent the detection matches in STIX format too.

That is where the STIX Sighting SRO and Observed Data SDO can help.

At this point you might be wondering about the differences between Sighting SROs and Observed Data SDOs.

- Observed Data: “These are the facts I saw.”

- Sighting: “Those facts mean we saw that threat intel object.”

Observed Data (SDO)

- What it is: Raw telemetry you saw (facts).

- Contains: Timestamps (

first_observed,last_observed),number_observed, and a list of SCOs (IPs, files, processes, URLs, etc.) inobject_refs. - Semantics: No judgment. It doesn’t say “malicious”—it just records that something existed/occurred.

- Typical producer: Sensor, SIEM export, EDR, honeypot, log parser.

Sighting (SRO)

- What it is: An assertion that a CTI thing was seen.

- Contains:

sighting_of_ref(usually an Indicator, Malware, Tool, Campaign, etc.), optionalobserved_data_refs(evidence),where_sighted_refs(who/where), plusfirst_seen/last_seenandcount. - Semantics: Judgment/interpretation. “This indicator/malware/campaign was observed here, at this time, this many times.”

- Typical producer: Detection pipeline, TIP, SOC workflow.

How they work together

- You collect Observed Data (e.g.,

ipv4-addr,urlfrom a log). - A rule/pattern matches an Indicator → you create a Sighting of that Indicator, and link the supporting Observed Data via

observed_data_refs

Which looks as follows on a graph;

Wrapping Up

STIX isn’t just a data model — it’s a detection language, and Indicators + Patterns are how you turn threat intel into something your SOC can actually use. The power comes from combining:

- Patterns – to describe malicious behavior

- Observed Data – to capture raw evidence

- Sightings – to confirm matches against intel

Patterns give us portable, sharable detection logic. Wrap them in Indicators, link Sightings, and you suddenly have not just lists of IoCs—but defensible, evidence-backed detection intelligence you can share across tools, teams, and organisations.

If you’re building modern cyber defence pipelines, learning STIX patterns can be a force multiplier in bringing intelligence and detection teams together.

SIEM Rules

Your detection engineering AI assistant. Turn cyber threat intelligence research into highly-tuned detection rules.

Discuss this post

Head on over to the dogesec community to discuss this post.

Open-Source Projects

All dogesec commercial products are built in-part from code-bases we have made available under permissive licenses.

Never miss an update

Sign up to receive new articles in your inbox as they published.